In a few days, suddenly, the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, the USA, Sweden Y Canada Several cases of a very rare disease have been announced that, although we have known about it for 50 years, had never before caused such an outbreak. The ‘monkey pox’ has entered the international public debate to make one thing clear: how little we have learned from the pandemic. This is what we know about the outbreak and, above all, what makes us start to be worried.

What is ‘monkey pox’ and why does it have us worried? It is a disease caused by a virus of the smallpox genus (variola viruses). Despite its name —which is due to the fact that we found it in macaques in 1958—, it is not usually transmitted by monkeys, but by other small mammals (such as rodents). As far as we know, contagion requires direct contact with blood, fluids or open injuries.

However, until now in humans transmission has always been (self) limited. We speak of “fever, myalgia, inguinal lymphadenopathy (swollen glands), and a rash on the hands and face, similar to that of chickenpox.” But, above all, we are talking about a relatively low mortality of 1% and a very low transmissibility. Generally speaking, nobody paid attention to monkeypox. Until now.

The situation is getting more serious. What is striking about this outbreak is that, until now, we had seen multiple cases of human-to-human transmission, yes; but we had not seen “sustained cycles of virus infection in humans” and everything seems to indicate that we are facing one of them.

But where did this disease come from? It is commonplace to say that ‘monkeypox’ is a very rare disease and, precisely for this reason, one wonders where the virus came from. It is just at that moment when we realize that, as Sergio Ferrer pointed out, “the Democratic Republic of the Congo reported more than 700 cases (and 37 deaths) in the first two months of 2022 alone.” These are the types of outbreaks that do not draw the attention of international public opinion until, finally, we have fifty cases in ten countries.

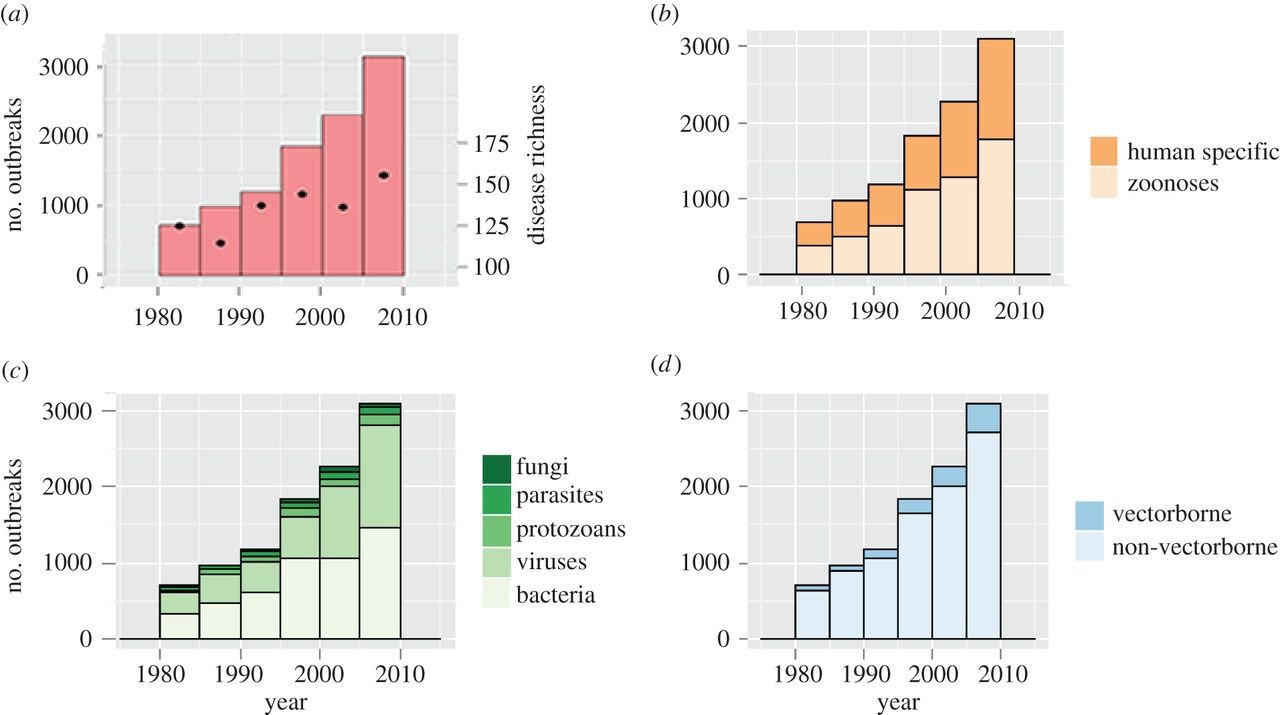

Why is this happening? The last two years have been a stark demonstration that our world is so interconnected that it has become an ideal breeding ground for infectious disease outbreaks. It is not just a ‘feeling’ generated by the pandemic. On the contrary, in 2014, researchers at Brown University identified all the infectious outbreaks that had taken place between 1980 and 2010. As we can see in the graph below, in those 30 years the annual number of outbreaks tripled worldwide and the causative diseases nearly doubled.

This emerging phenomenon meant that, in 2007, the World Health Organization began to apply new international health regulations thanks to which it had a greater capacity to create international policies against international diseases. For what concerns us, it was the birth of “public health emergencies of international importance”. Since then it has declared five (although the last one, that of COVID, went a step further and became a “global pandemic”).

But what strikes me as most significant is that, with the exception of the new coronavirus, none of those emergencies was caused by a new and unknown infectious agent, but by a subtype of the influenza virus (a virus that we have known for at least 2,400 years). ), by polio (described in 1789, but which already affected the ancient Egyptians), by Ebola (discovered in 1976) and by Zika (known since 1947). Monkeypox, for example, we have known about since 1958.

and it gets worse. In 1995, Stephen Morse described the fundamental factors that were driving the global emergence of infectious diseases. There are two vectors that are especially significant: on the one hand, environmental changes (something that can be seen in how changes in aquatic ecosystems have caused the growth of diseases such as Argentine hemorrhagic fever, schistosomiasis or Rift Valley fever ) and the increased movement of goods and people around the world, on the other hand. The introduction and proliferation of HIV, Denge or Zika, or the appearance of airport malaria are good examples of the latter.

However, this does not explain everything.. It is true that these factors have only deepened since 1995, but by themselves they do not explain what is happening with monkeypox. The drop in cross-immunity that the smallpox vaccine gave us is a key factor, yes; but for us to be in this situation, there has had to be a change in the dynamics of virus transmission. In other words, something has changed that has allowed it to ‘become independent’ from animal reservoirs and has made it easier for it to settle in human populations. The question we now have to answer (and in a hurry) is what else has changed?

Image | CDC