Human beings have been telling stories long before they started recording their own. During most of that time, tales, legends, and epics were passed down orally. Even after writing was invented and even after inventions such as parchment, paper or the printing press made it popular, humanity did not stop transmitting stories by word of mouth.

But the ways of transmission oran have changed a lot. From epic tales to the theater and then to radio soap operas and, in a way, the cinema. In recent years, a new form of oral transmission has emerged: the audiobook. It is also a format that is gaining audience by leaps and bounds since it was introduced on our smartphones.

A rising market

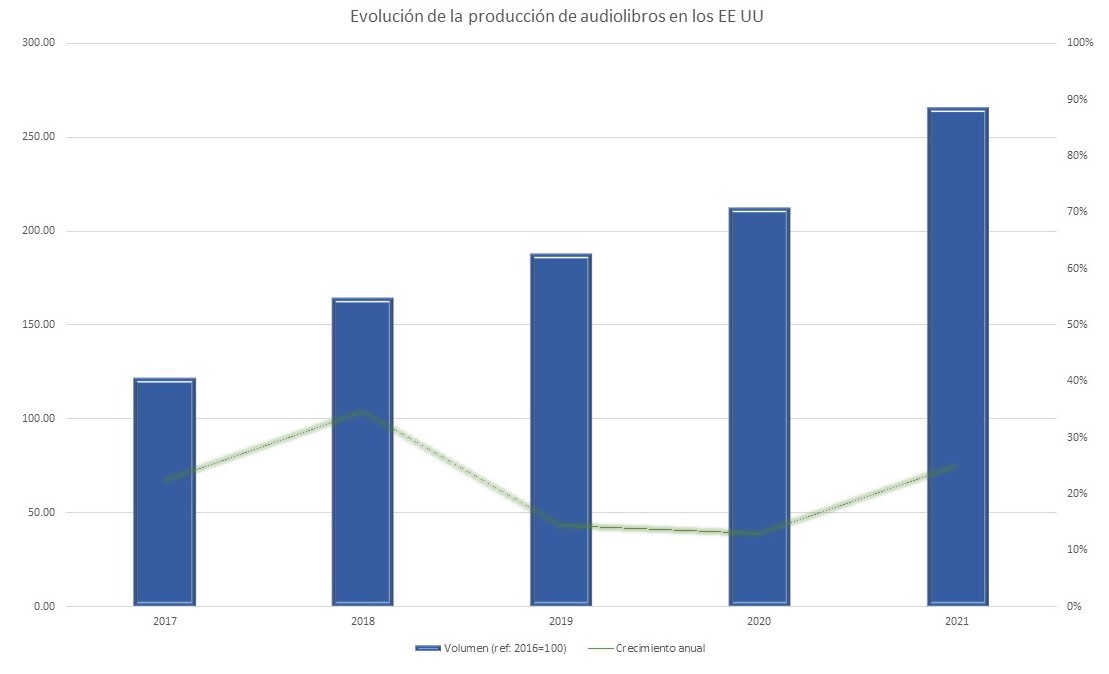

Audiobooks are thus gaining popularity. Spotify is the latest company to jump into this arena (although this jump has been cooking for a while), and it seems that there is room for more. The turnover of this sector in the United States (according to data from the industry itself) was 1,600 million dollars in 2021, 25% more than the previous year. This figure would have marked the tenth consecutive year of growth above 10%.

The increase in the number of audiobooks published in 2021 over the previous year was more modest: 6%. Even so, this meant that 74,000 new titles were reached in one year. It’s not just a sales issue. Again according to the industry, audiobook readers listened in 2021 more than twice as many hours as they listened in 2017.

Data: Audio Publishers Association.

In Spain the market is also growing. Although delayed, the Spanish-speaking market is recovering ground, and in 2021 it grew by 137% according to Bookwire, a company also in the publishing sector itself. Audible, Amazon’s brand in the audiobook segment, is the one that dominates this market. With 80% of the catalog of audiobooks in Spanish, it will surely be the rival to beat for Spotify.

The audiobook sector is as closely linked to the publishing world as it is to the technological world. This makes it a very dynamic and changing market. To the point that someone might think that it is a new market. Nothing could be further from the truth: The first references to audiobooks date back to the early 1930s.

The first experiments are even older. Thomas Edison tried to record narrated versions of literary texts in the mid-19th century, but with little success. In 1931, the United States Congress passed legislation to promote audiobooks. so that blind or disabled people have access to reading in American libraries.

The first push to the industry would come with the cassettes. These tapes turned audiobooks into laptops, first in cars and then in Walkmans. Then came the CDs and finally the MP3s. The arrival of smartphones, dedicated applications and the streaming are the factors that have given audiobooks their second (and strongest) push. The audiobook has even ceased to be a “dump” of the text to become a medium with its own identity, and there is still a long way to go.

The user of audiobooks has also changed, how could it be otherwise. First, technical development has notably lowered production costs of this format and with it its price for the consumer.

The audiobook user is younger today. Audiobooks also seem to have balanced reading habits somewhat, at least in America where one in four books went to men while audiobook purchases are split almost evenly between genders.

Again according to a study conducted by the audiobook industry, audiobook consumption is positively correlated with “traditional” reading habits. That is not to say that consuming audiobooks encourages reading, it is more likely that those who are regular readers are more likely to combine their “conventional” reading with listening to audiobooks.

Comparisons are hateful… and also useful

Perhaps we can explain part of the audiobook phenomenon by referring to some more or less direct antecedents. Audiobooks are currently intermingled (also in their success) with another form of oral transmission: podcasts. And these are in turn heirs of the radio. Radio was possibly the first authentic mass communication medium, capable of reaching all corners at a time when illiteracy was still high.

Radio generated an immense social impact and the events that marked the 20th century could not be understood without its arrival. However, its impact on a personal level, in the development of each individual, did not seem to be as great as expected at first.

The importance of experience

The million dollar question, what does science say about it? Before consulting science we can listen to our intuition: No, it’s not the same. But the differences may be smaller than we think.

One of the ways that audiobooks can affect our reading is our level of concentration. We cannot take this for granted (who has not had to go back two paragraphs, or two pages, in the reading after realizing that they have been reading distracted for several minutes), but in general we concentrate more on reading “with the eyes”.

It is very common to listen to audiobooks while we perform other tasks. The experience and retention will not be the same, but the truth is that nothing prevents us from using concentrated audiobooks, it is something that will depend on the use made of them.

Reading, on the contrary, requires us, if not concentration, at least full dedication. Unless we take advantage of a trip to read, conventional reading cannot be combined with other activities. It is precisely in this fact that each modality takes us in a direction where the differences between both experiences arise. And where the differences arise between what we retain when reading and what we stay with when listening.

But… is reading the same as listening?

Various studies have been carried out on how we retain information after reading in different formats, but studying the effects of audiobooks is a more difficult task than it seems. The results vary, among other things because they try to answer different questions. For example, the analyzes can compare between reading a text and listening to it, but they can also measure what happens if you listen and read at the same time. Results may vary between fiction and non-fiction texts, their level of difficulty, or the age of the participants and their experience as readers. Some studies have even measured the motivation of the participants together with their understanding of the text read.

Thus, some studies found that there was no difference between conventional reading and (attentive) listening to a text, not even between these modalities and the combined one. This seems to be the most widespread theory, although it is far from being universally accepted.

One study, for example, compared the levels of comprehension of a (non-fiction) text between two groups of students. After performing a test, he observed that the level of retention of information was higher in the group that had read compared to the group that had listened. Motivation was also higher in the first.

And what happens in the long term? Here’s an important question… for which we don’t have an answer yet. Long-term studies are difficult in this case. Reading habits are something that cannot be controlled in the laboratory. That is why analyzing what happens in the long term with our reading ability or our attention range when we substitute reading for listening is difficult. Any study will have to face the fact that listening is very often a complement and not a substitute for traditional reading.

There is a time in our life when this substitution could occur. Reading habits usually appear in childhood and adolescenceso some experts worry that access to audiobooks creates a situation where students simply take the easy option.

Here the key distinction must be made, knowing what the objective of the reading is. When the goal is to improve reading skills, there is no doubt that there is only one way to achieve it, and that is by reading. Once this ability has been acquired, studies again indicate that there are few differences between audiobooks and conventional reading, since what can be lost in concentration is gained by being able to listen to the pronunciation of words and intonation of sentences.

There is a problem to take into account when analyzing the studies carried out around audiobooks, and that is the language. How many times have we heard that “I learned more English through series and video games than in class”? It’s not nonsense. The English language, unlike Spanish, has some significant differences between writing and pronunciationwhich means that listening can help retain words, especially when they are new and have counterintuitive pronunciations.

The problem arises from the fact that this advantage of audiobooks is less evident in other languages, but most of the studies done regarding the advantages and disadvantages of audiobooks can present a “language bias” if we try to extrapolate them to our language. . In our context, audiobooks still have the potential to help, for example, in learning English as a foreign language.

From the beginning, or especially before they became popular, audiobooks have been tools with which to bring reading closer to people with “conventional” reading difficulties, the most obvious case being that of blind people. But even in this field he has had his detractors. In this case, critics were concerned that audiobooks would impair the ability of the blind to read braille.

Can we draw conclusions?

Audiobooks are becoming a separate medium. Without being able to compare with film or television adaptations, they present their own features and have tools with which to distinguish themselves, such as the use of a variety of dubbing. That is why comparisons are difficult, a matter of taste in the end.

As Frank McCourt, author of Angela’s Ashes, explained, for him the most complete reading experience is the traditional one, “but I’d rather people listen to the book than not at all.” Let’s hope we don’t have to choose.

Pictures | Jukka Aalho, Andrea De Santis, Karolina Grabowska